The Weird World of PS 231

This post collects the various materials I’ve developed for an introductory game theory course taught at the University of Illinois. I'll just call it by its course name: PS 231.

The average political science student is none too happy about having to learn game theory. Sure, it sounds cool at dinner parties—but then you realize you're studying a suite of mathematical concepts, techniques, and models designed to deepen our understanding of strategic interdependence. And I just used the "math" word. THE MATH WORD!

Nevertheless, game theory is capable of delivering real insight into politics. Political scientists use game theory to understand phenomena like lobbying, wars, voting, center-periphery tension in developing states, trade disputes, legislative bargaining, and all sorts of other things. So, it behooves students to learn enough of the method to appreciate the substantive insights that method provides.

So how do we excite students about learning a method—and a mathy method at that—when they often care more about what they know than about how they came to know it? This is the primary pedagogical challenge behind PS 231. And I've tried to take on that challenge a few different ways:

- by employing a (somewhat) flipped classroom modality, where students watch a lecture video before the week's scheduled meetings and then work on activities thereafter;

- by focusing on storytelling, particularly by setting the in-class activities in a fictitious world called Olympia;

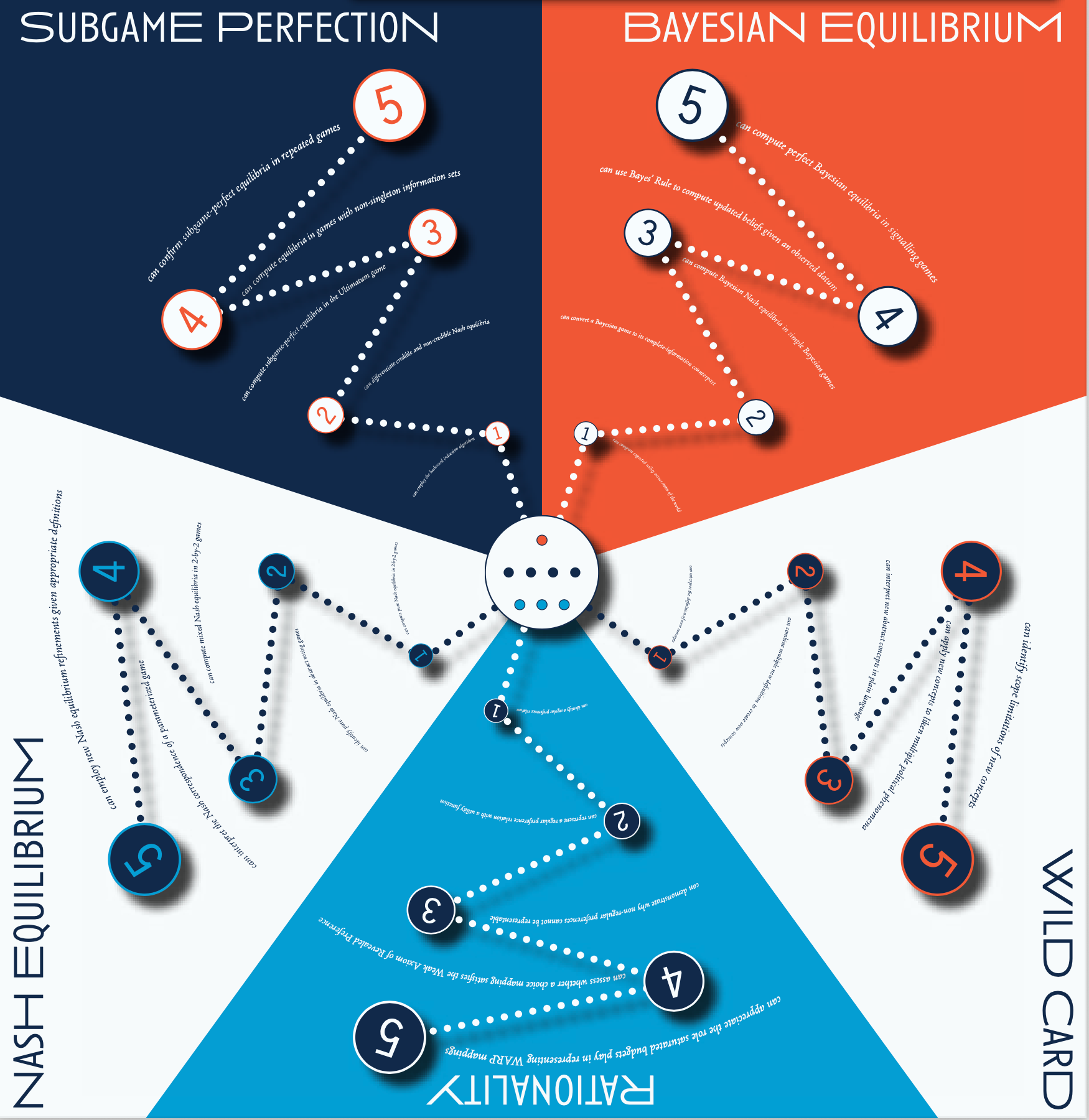

- by using some elements of formative assessment and gamification to encourage students to remain engage without getting too obsessed about each and every one of the myriad technical details underneath game theory;

- by adopting a unified visual theme based on UIUC brand standards and some unique quirks that suit the course; and

- by inviting students to be curious, to have fun, to fail usefully, and to struggle without suffering.

So in this post, I'd like to share the materials for the course.

The Syllabus as an Invitation

Naturally, the first thing a PS 231 student sees is the syllabus.

You probably weren't expecting 21 pages of nonsense, were you? But dear reader, it's got to be inviting. You've got to go Full Dumbledore. There is no such thing as 50% Dumbledore. We're doing this or we're not.

What purpose does all the nonsense serve?

- It establishes the tone: the academic tone, sure, but also the visual tone. Illini Blue and Orange dominate, as does the Alma Mater statue (an important landmark on campus).

- It invites the students to the nonsense by embodying the nonsense.

- It introduces basic course mechanics, of course, along with the other basic information one usually sees in a syllabus.

- It lets the students know that this is going to be an experience.

A few highlights for those of you who don't like pineapple on their pizza:

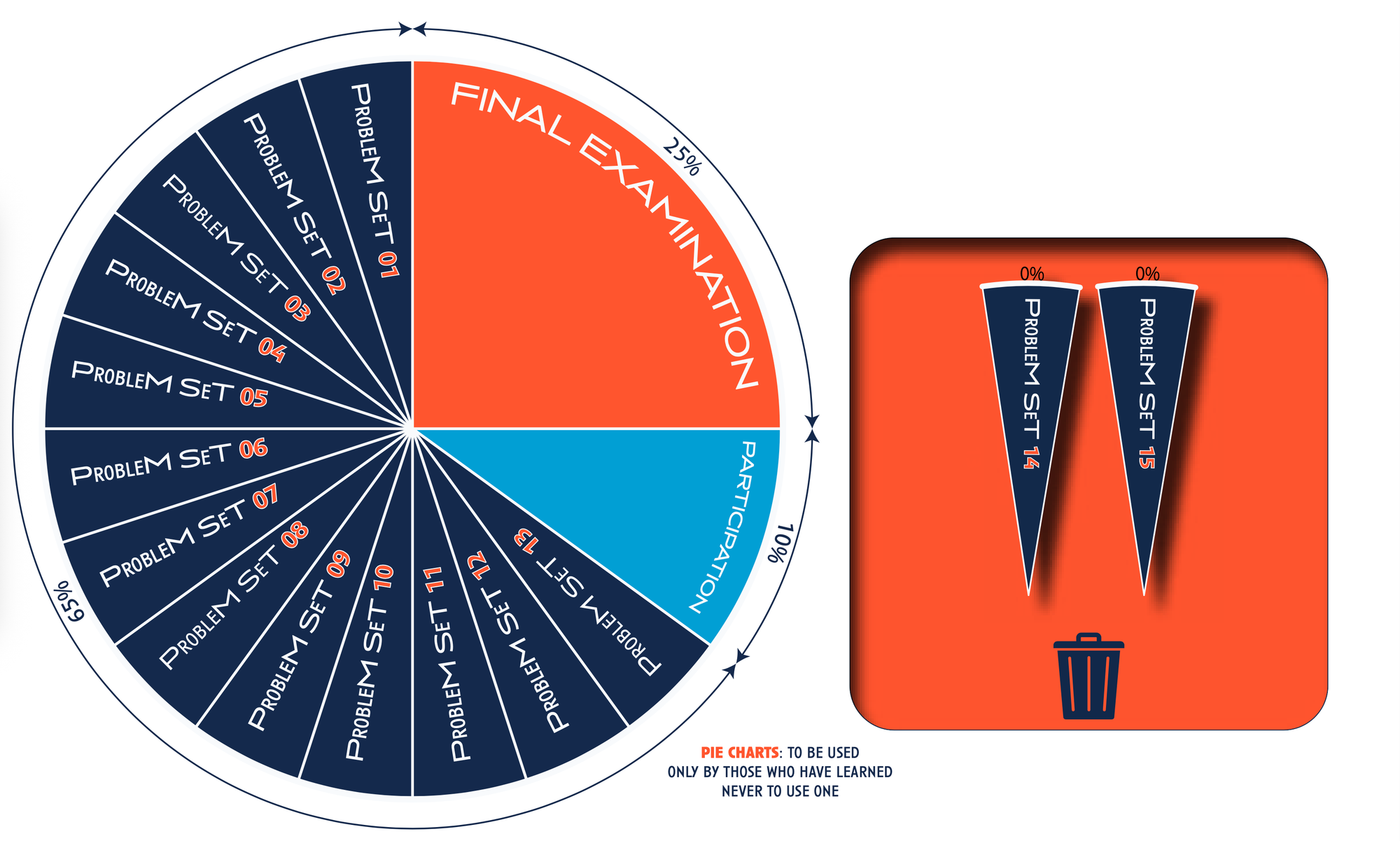

Evaluation

As the pie chart so clearly (?!) demonstrates, students would do well to focus on the weekly problem sets. There are fifteen in total, and they can drop two. All of the problem sets are graded on a pass/fail basis, so each one is basically 5% of the work it takes to get to 100% of the points. And they can even re-do problem sets they fail, so long as they earn the chance to do so (here's where formative assessment and gamification kick in!).

And just to avoid all possible confusion, the students even see what will be on the final while they're still reading the syllabus.

Philosophical Appeals

Look, I teach with a point of view and don't apologize too much for doing so. For starters, I teach like a hippie. The hearts, they're real. Let's love one another, people.

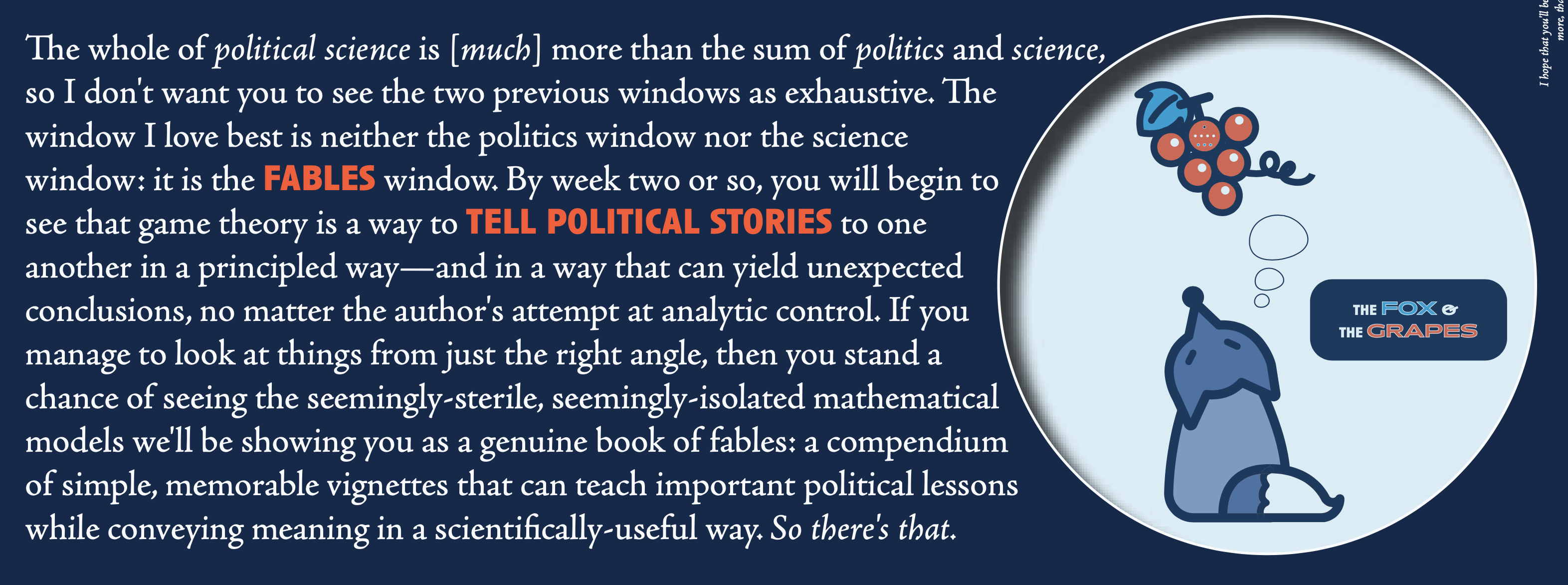

But there are also less obvious philosophical appeals; for example, I tend to view game theoretic models as tools we use to see the world (the semantic view of scientific models), but they also happen to have linguistic content. Economist Ariel Rubinstein, taking the same idea, likens models to fables. And that's where the storytelling idea really starts to kick in. This needs to be signposted to students, and not with any real subtlety.

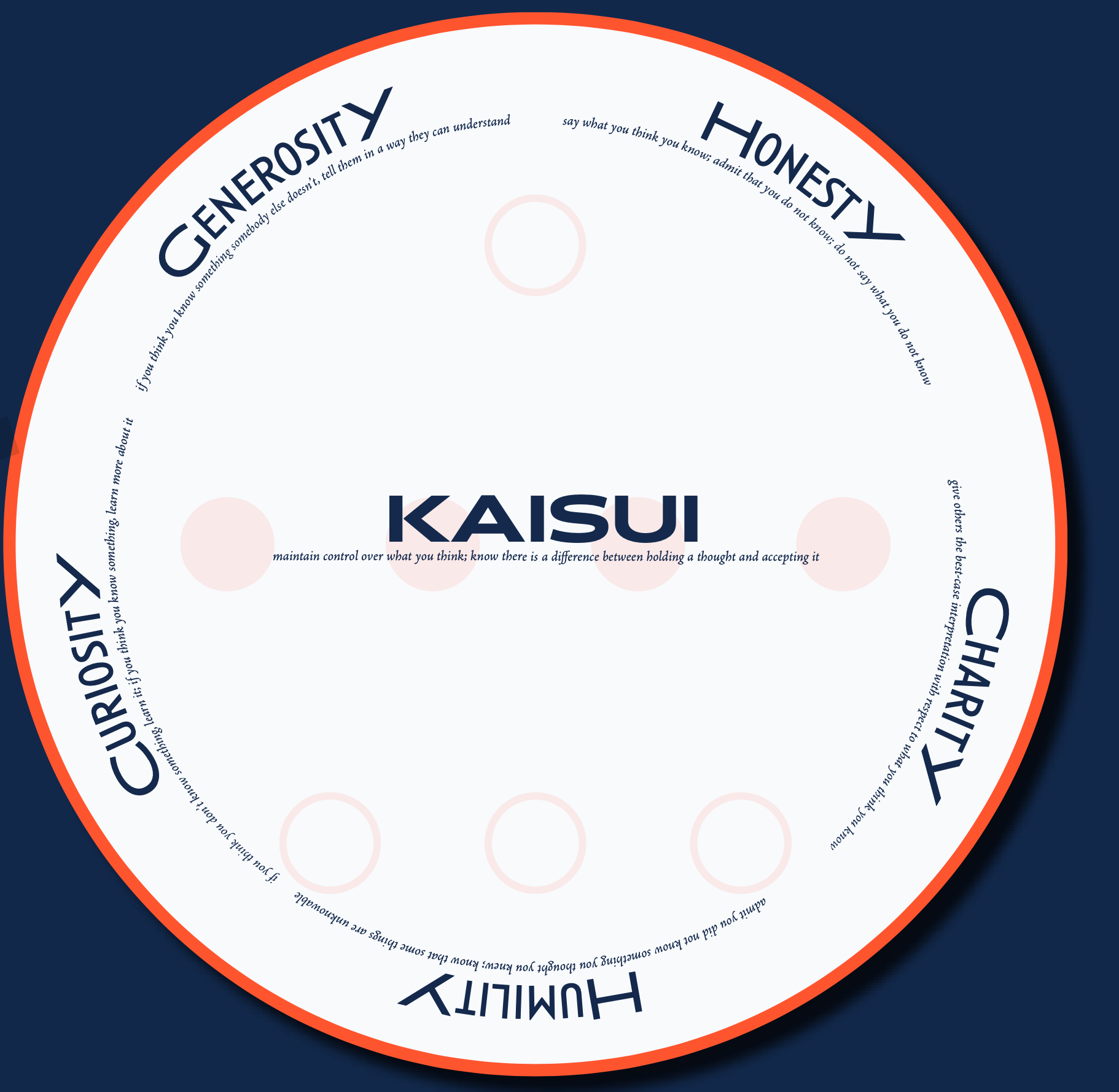

Heck, I even tell them I care about virtues!

Storytelling

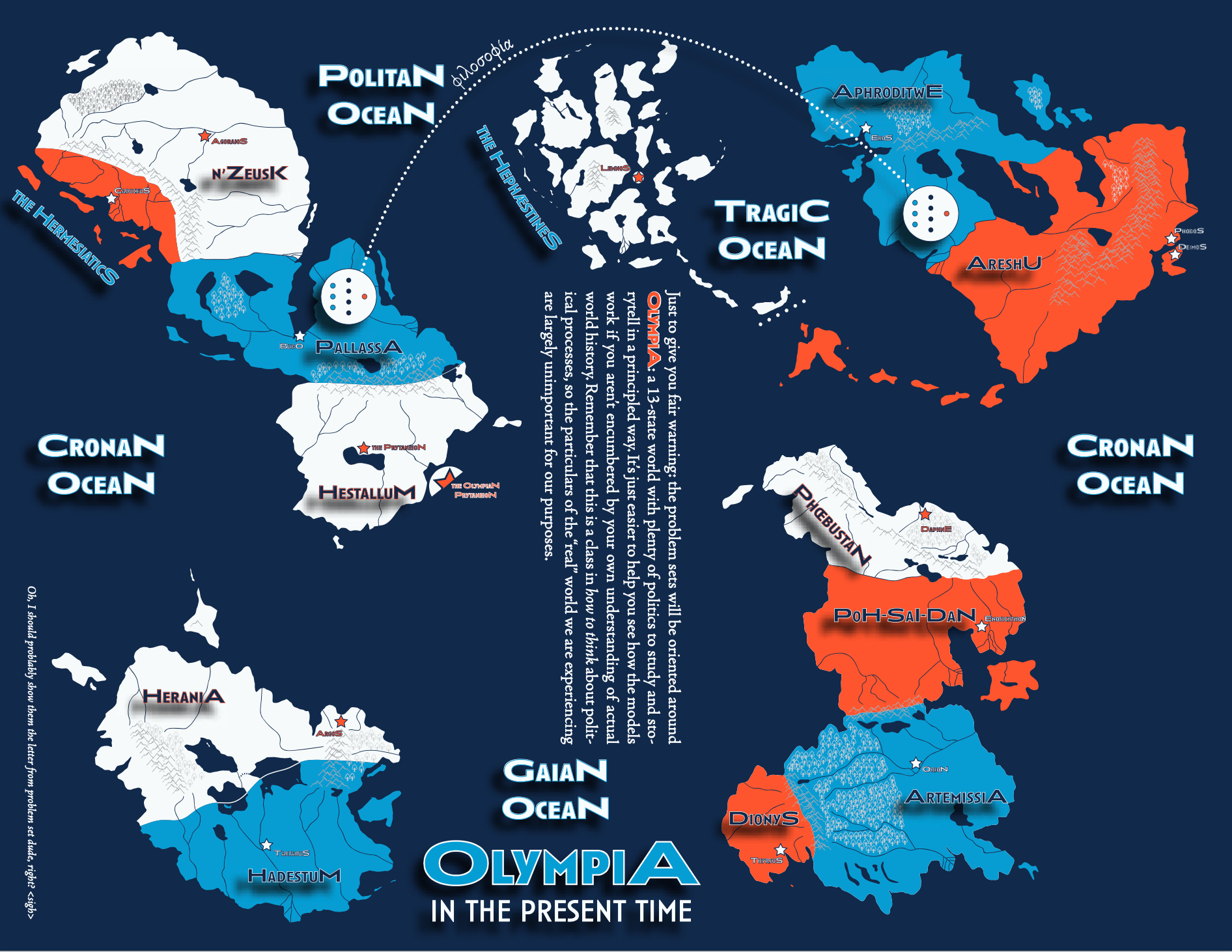

Beyond the fox and the grapes as mentioned above, the students get their first introduction to Olympia, the fictitious universe where the problem sets live. Like Fred Rogers's Land of Make Believe, these provide a laboratory for ideas in practice.

And they even get to meet Bizarro Me, the narrator of said problem sets:

Gamification

How do we get students to care about more than just grinding out problem sets and the final? In PS 231, they're incentivized to stay engaged through ALMA tokens. They can earn them by doing well on problem sets, sure, but also by doing things like asking cool questions in class, presenting models at the end of the semester, being helpful at office hours, and so on. These tokens can be used several ways:

- for 5 ALMAs, you can re-do a problem set you failed;

- for 20, you can "buy" a pass on a failed problem set (so basically you can get a pass on the cheap if you put in the work to fix your mistakes, or you can get one expensively if you're feeling a bit lazy); or

- for 20, you can "buy" off one fifth of the final exam.

One of these days I'm going to have an NFT auction for spare ALMAs, so that they actually become a real token.

Students can also earn ALMAs by coming to class often and hearing the Yellow Book Question of the Day. These are questions drawn from a delightful book called The Last Unknowns, edited by John Brockman. Honestly, one big theme in the course is that questions are cooler than answers, and this book is full of really cool questions that students are encouraged to go home and think about. Write up enough answers, and you get an ALMA token.

Video Lectures

So, the students watch a lecture video prior to each week's activities. (Or at least, they're told to do so.) I didn't know anything about how to make a lecture video when COVID hit, and I still don't know all that much about it. But, I managed to put in enough elbow grease to have a serviceable set of lectures available for the course.

I'll be dropping the videos here, so I won't bloviate too much about them. But in broad brushstrokes:

- Making a set was critical. It gives the students some personality on my end, and I've found that they like keeping track of the details for how the set evolved throughout the semester. For example, Lecture 02 involved use of a few bottles of pop—or as some of you barbarians call it, "soda"—and those bottles remained on the set for the rest of the lectures. There are a few other little details like that.

- Overlaying math over top of this ugly face was a really good idea. But, I think keeping the face involved was still important—these aren't just math animations. They're me using the animations to try to talk to the students. And yes, that means it looks like this:

- They're in 4K, they have soundtracks, they have good sound, etc. If you're going to subject a student to an hour and a half of game theory, at least make it look and (especially) sound good! I definitely overspent on equipment—more on how the videos were made in a future blog post, perhaps—but at least all the Adobe software was covered by UIUC licenses.

Lecture 01: Encoding the World (Sets, Functions, and Logic)

clearly i did that opening animation all by myself.

Lecture 02: Contemplative & Competent (Rational Choice)

mmm coke booooo pepsi

Lecture 03: Uncertainty (Expected Utility I)

don't tell the governor about the lottery research please and thank you

Lecture 04: Risk (Expected Utility II)

or: never trust a triangle

Lecture 05: Bargaining & Optimality

the metafable of the introspective analyst was a happy accident

Lecture 06: Games

heaven forbid, games in a game theory course...?!

Lecture 07: Nash Equilibrium I

whatever you do, do NOT ask ron howard for help with this

Lecture 08: Nash Equilibrium II

any baseball teams hiring a strategist?!?!

Lecture 09: Time (Extensive Form Games)

probably my best chess match ever

Lecture 10: Credibility (Subgame Perfect Equilibrium)

BOCA! BOCA! BOCA!

Lecture 11: Repeated Games

who needs yin and yang when there's yinz and y'all?!

Lecture 12: Information (Bayesian Games)

when you control the mail, you control...

Lecture 13: Alpha! (Bayesian Equilibrium)

are you tired of bach yet? how about stravinsky?

Lecture 14: Poker

training the next generation of derelicts

Problem Sets

And after watching the video, the students have the basic skills required to jump into the problem sets. But, we use our scheduled class time for Q&A.

Each problem set starts with a little introductory vignette from Socrates, the narrator. He's always got one problem or another to figure out, and he's very, very, very needy. Sometimes these problems are political, like understanding how two states negotiate prior to the decision to go to war. Some are trivial, like understanding why his dog picks certain toys or which book to buy for his niece. We hopscotch all over Olympia, which is handy because certain countries have game shows that are JUST LIKE GAME THEORY PROBLEMS.

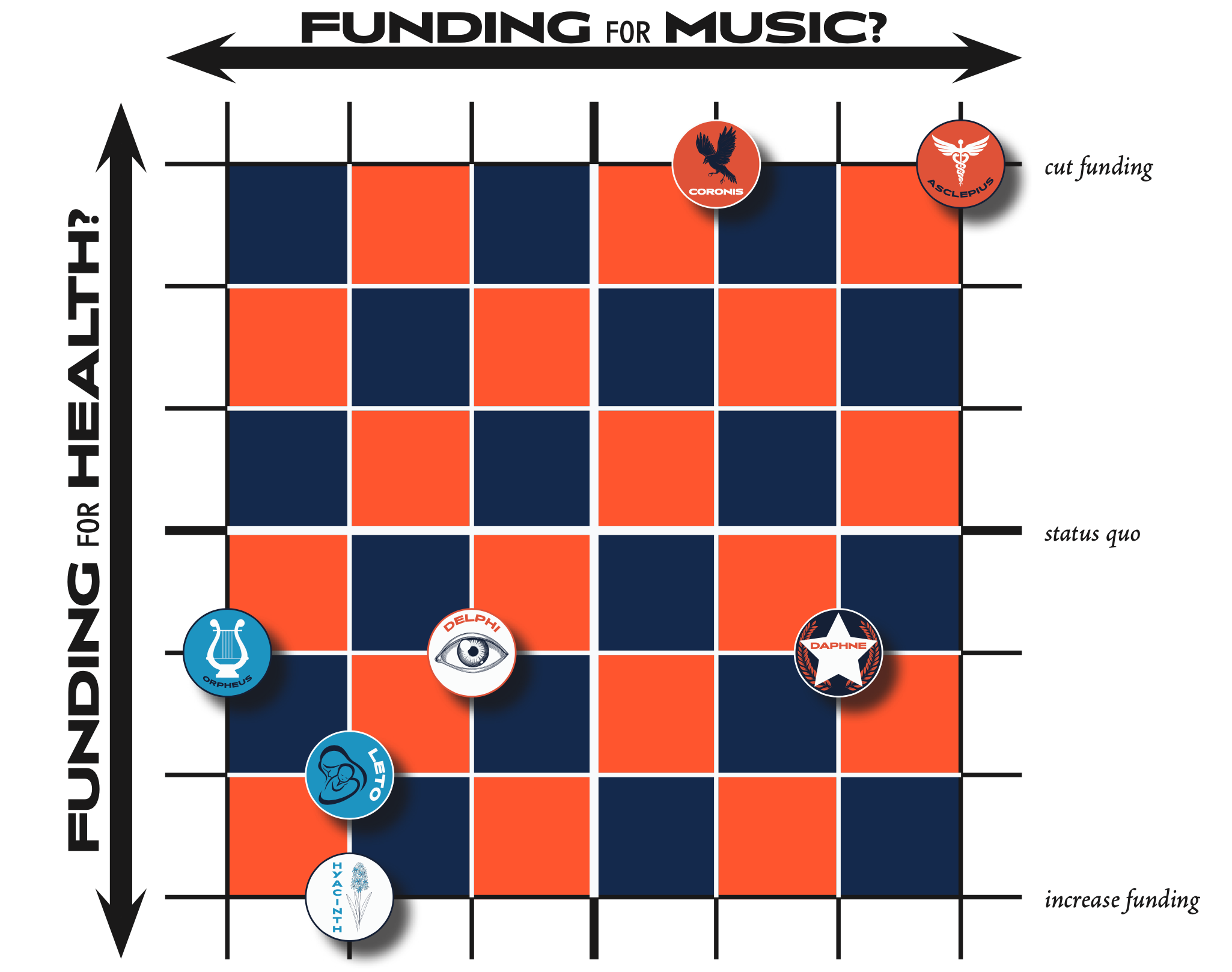

These problem sets have the same visual style as the syllabus and the lecture videos, and they encourage students to think abstractly about real problems. Since each country in Olympia is inspired by a different ancient Greek deity—Pallassa for Athena, n'Zeusk for Zeus, and so on—the storylines and concepts often allude to classical stories from mythology.

I think my favorite is Problem Set 05, which features two political parties in the country of Herania (named for Hera, of course) on the continent of Geneseo.

The parties are the Peacocks and the Cows—two animals linked to Hera in ancient Greek tradition.

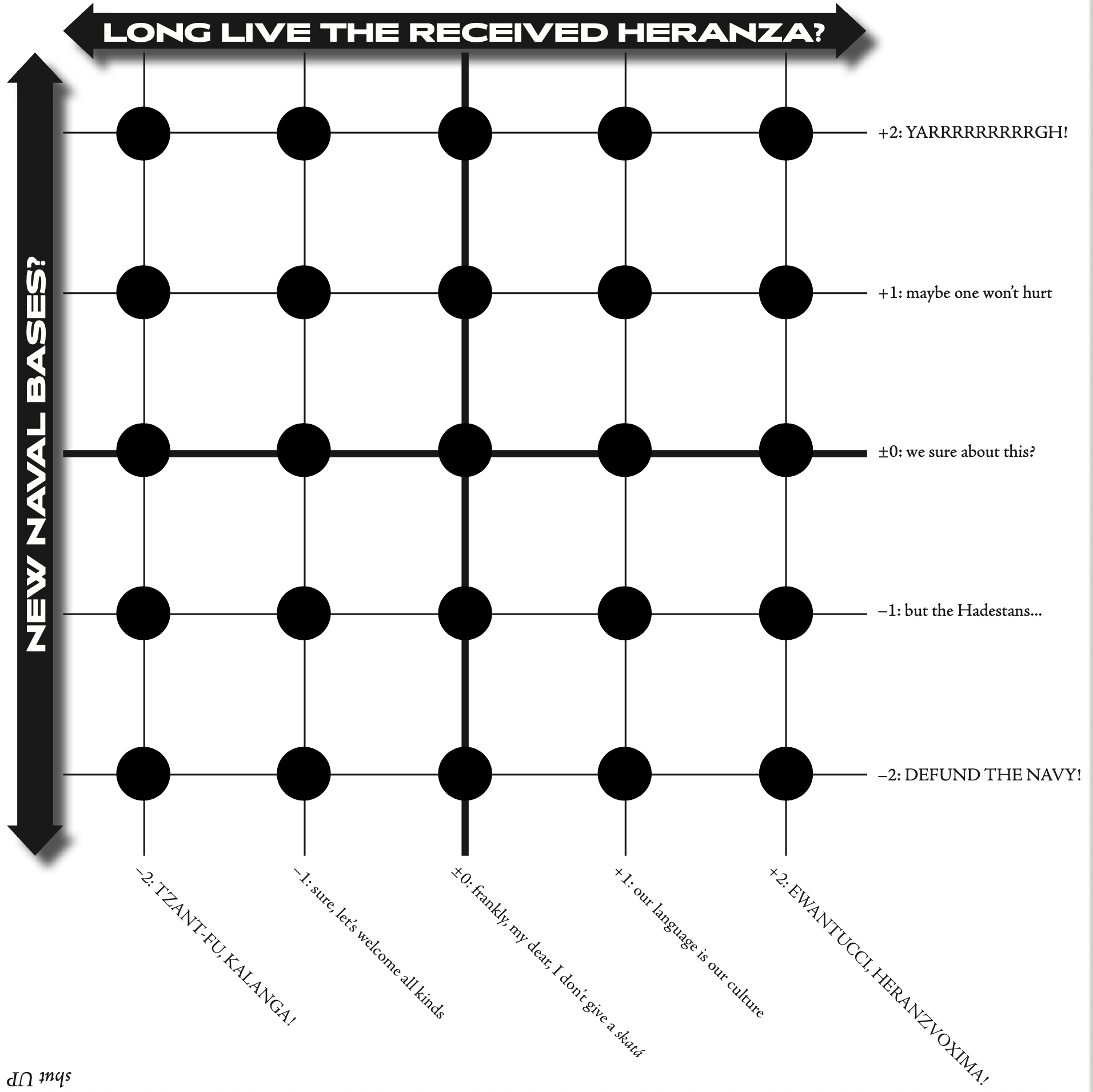

The Peacocks and Cows are trying to figure out how to navigate a two-dimensional policy space: one dimension is social policy, and the other is foreign policy.

And remarkably, their hijinks in this space wind up being relevant for a particular quote by a particular philosopher:

Though this problem set is particularly narrative, they all have some of this flavor. I'll dump them below in case you want to give them a try!

And then Problem Set 15 involves students making their own problem set about whatever they want to—their own lives, or real politics, or fake worlds, or whatever. The best models wind up being presented to the class (and then get used other ways, but that's not important now. Cryptic!)

Bonus Content: PS 231, The Playlist!

This past semester, a student asked me about study music. My answer wound up being a playlist, and I hope you'll enjoy it. (Not all music is good to study to, but there's some good stuff in there, and it's got a bit of an arc to it, and CAVEAT EMPTOR to you Esperanto speakers out there.)

USE APPLE MUSIC PEOPLE IT JUST SOUNDS GOODER

Wrapping Up

Anyway, I've succeeded in my task of collecting all the materials for PS 231. And that's excellent (nice job, Rob! Thanks, other Rob!). But what makes PS 231 so dear to me isn't all this nonsense I made for it: it's how the students respond to said nonsense. Sure, many of them are uncomfortable with a course that's designed to be...weird. High maintenance. Eager. Curious. Rigorous. Creative. But you'd be surprised just how many of them lean into The Weirdness, how quickly they lose themselves in the details of Olympia, and so on. I'm also struck by how good their notes are when they watch the video lectures—like seriously, they are really great note-takers outside of traditional lectures. It's a joy to be their teacher.

Hopefully some of The Weirdness has resonated with you, as well. Feel free to steal tricks as you see fit, or share the ones you've got.